Given that Inge lives in New York, and I am now living in Colorado, an in-person meeting wasn’t possible, but we scheduled a time to speak over the phone instead. By speaking with Inge and reading her powerful autobiography entitled I Am a Star: Child of the Holocaust, I learned about her family and the years they spent in Terezin.

Inge was born on December 31, 1934 in a village called Kippenheim, located in South-West Germany in the Black Forest region. Her family had lived in Germany for over two hundred years, and her father, Berthold, served in the German army during World War I. Disabled during the war, he was honored with an Iron Cross for his service and subsequently developed a successful textile business. He and his wife Regina and daughter lived in a comfortable home and had good relations with both their Jewish and Christian neighbors.

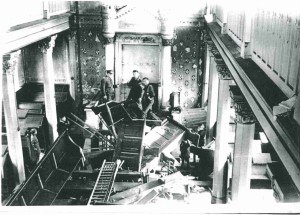

Everything changed when Inge was three years old. Though a young child, Inge still remembers how her grandfather and father were arrested and taken away to the concentration camp Dachau, along with all Jewish men over the age of sixteen. She remembers the windows of her home being smashed, and running to the backyard shed to hide from the raging mob. The synagogue was badly damaged in the Kristallnacht riots. After a few weeks, her grandfather and father returned home, but nothing would be the same. Inge’s father lost his business and sold his home in Kipperheim. The family moved to Jebenhausen, where Inge’s grandparents lived. Soon after the move, Inge’s grandfather died. He ended his life bitterly disappointed in the country he had once loved.

Inge started school at age six and was forced to attend a separate school from the Christian children. She needed to walk two miles and then take a train to reach the nearest Jewish school. She had to make this journey for six months, when transports began and she could no longer attend school. In 1942, when she was just seven years old, Inge, her parents and her grandmother were assigned on a transport east. Her father requested that his family be spared, given his status as a disabled veteran. His request was granted, but the Nazis refused to remove Inge’s grandmother from the transport.

In August 1942, Inge and her parents were assigned for another transport, despite her father’s veteran status. Their money was stolen, they were driven from their apartment and taken to Stuttgart, where they had to sleep on the bare floor of a large hall for two nights. Then they were taken to their final destination, Terezin.

References

Books by Inge (available on Amazon)

I Am a Star: Child of the Holocaust

Beyond the Yellow Star to America

www.ingeauerbacher.com