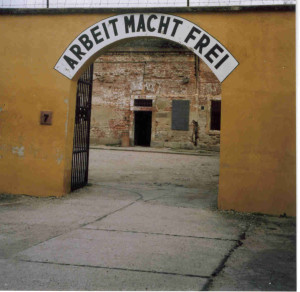

The interrogation and subsequent imprisonment of these men and their families in the Small Fortress of Terezin would come to be known as “The Artists’ Affair”. What follows are the stories of these men, beginning with Leo Haas, the one member of the group who survived the war.

Leo Haas was born in 1901 in Opava, Czechoslovakia and was interested in art from a young age, showing promise in painting and as a piano player. As a teenager, an art teacher recommended that he continue his art studies, and Leo moved to Karlsruhe, Germany to study at an art academy there. To fund his studies, Leo played the piano in local bars and restaurants – and painted the scenes he observed around him. In 1921 he moved to Berlin where his finished his studies and began working in a graphic design studio. He spend time in Paris and Vienna before marrying Sophie Hermann in 1929 and settling in his hometown of Opava. Haas became an established portrait painter and director of a local printing house, and was also known as a caricaturist.

Leo’s first encounter with the Nazis came in 1937, who declared his caricatures “degenerate” and “Communist”, which foreshadowed the events that would happen at Terezin. Haas, his second wife Erna, and her family were sent to Terezin at the end of September 1942. Haas was soon transferred to the graphic department of the ghetto, where his primary task was making architectural charts. Other well-known artists also worked in the department, including Otto Ungar and Bedřich Fritta, who would become a close friend of Haas. The men were often able to visit other parts of the ghetto, and they secretly began to paint and draw what they observed. Haas depicted transports, scenes from the ghetto café – where no food or drinks could be found, performances, bread rations being transported in a hearse, and many other aspects of life in the camp. He was known for being very politically minded, but known for his compassion and unflinching depictions of ghetto life in all its brutality.

He created a secret compartment in the paneling of the wall of his barrack where he hid many of his works. The works remained hidden during Haas’s interrogation and imprisonment in the Small Ghetto of Terezin, where Haas was sentenced to hard physical labor. After three and a half months, Haas and Fritta were again interrogated and accused of distributing Communist propaganda.

At the end of October they were sent to Auschwitz for their supposed crimes. Fritta was ill with dysentery and died a week later. Haas was soon transferred to another camp called Sachsenhausen where he was put to work in a counterfeiting unit due to his artistic talents. He was transferred twice more before being liberated by the Allies on May 5th, 1945. His wife survived the war but was in very poor health, and would remain sickly for the rest of her life. They adopted Fritta’s son Tomáš and moved to Prague, where they lived until Erna’s death in 1955. Haas then moved to East Berlin where he remarried, and worked as a caricaturist and cartoonist. He also exhibited his art around the world, up until his death in 1983.

Not long after the war, Haas bravely returned to Terezin in the hopes of recovering the paintings he had hidden in a wall panel of his barrack. He found all the paintings he had hidden there, as well as some of Fritta’s works, works of art that showed the world the truth of Terezin.

Further Reading

The Artists of Terezin by Gerald Green

http://art.holocaust-education.net/explore.asp?langid=1&submenu=200&id=14

http://www.theholocaustexplained.org/ks4/the-nazi-impact-on-europe/theresienstadt-a-case-study/leo-haas-living-culture-in-the-ghetto/#.WPPA3NLyvIU

http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/last_portrait/haas.asp