It is December 1941, and in her barrack, a twelve-year-old girl paints a cheerful picture of two children building a snowman. She hopes the lighthearted scene will lift her father’s spirits. For weeks they have been confined to this ghetto. Worst of all, this girl has been separated from her father. She misses him terribly, but the most she can do is smuggle the drawing to the men’s barracks. She is surprised by her father’s reaction. He doesn’t want her to paint pictures of happier times. Instead, he urges her, “Draw what you see!”

It is December 1941, and in her barrack, a twelve-year-old girl paints a cheerful picture of two children building a snowman. She hopes the lighthearted scene will lift her father’s spirits. For weeks they have been confined to this ghetto. Worst of all, this girl has been separated from her father. She misses him terribly, but the most she can do is smuggle the drawing to the men’s barracks. She is surprised by her father’s reaction. He doesn’t want her to paint pictures of happier times. Instead, he urges her, “Draw what you see!”

From that day on, this young girl draws what she observes around her, scenes of daily life in the Terezin ghetto. By doing so, she chronicles the truth of Terezin.

Early Life

The girl’s name is Helga Weiss, and she was born in Prague on November 10, 1929. Until recently, she lived in Prague with her parents Irena, a seamstress, and Otto, who worked at the state bank of Prague. After the Nazis came to power, Otto lost his job and the family struggled to make ends meet. Helga had to leave school and continue her studies privately with other Jewish children. The Jews of Prague lost more and more rights and then were deported from their homes.

Helga and her parents arrived in Terezin in December 1941. For most of the time, Helga lived apart from her parents, in a building designated the Girls’ Home. Helga kept a diary of life in the camp and created countless drawings and paintings of what she saw around her.

Life in Terezin

Helga’s paintings show remarkable artistic talent and are rich in detail. She painted her parents in their apartment in Prague taking an inventory of their possessions, which they had to hand over to the Nazis. She depicted the rows of bunks in the Girls’ Home, an opera performance in the ghetto, and a haunting image of a girl receiving her summons to join a transport. People often received a summons at night, and the girl sits in her bunk in the dark, awakened by a flashlight shining on her.

In her diary, she wrote about a performance organized by some of the girls in her barrack. Helga and the other girls sang together, performed a short play, and experienced a rare moment of beauty in the ghetto. With tears in her eyes and her mind filled with images of her home, Helga realized that for a fleeting moment they were free.

The Hardest Good-Bye

Helga witnessed the exponential growth of the camp population, the endless transports, and the Red Cross visit in the summer of 1944. After the visit, the terrifying transports east started again. Her friends were sent away and then in October 1944, Helga’s father was assigned to a transport.

One of the most tragic and haunting moments in the diary is when Helga and her father said good-bye. She hugged her father close, resting her head on his chest so she could hear his heart beating. Then as he walked away, Helga’s father turned and waved at her with a strange expression on his face. He tried to smile, but his mouth was trembling and all he could manage was a kind of grimace. Helga called out to him, but then she lost sight of him in the crowd.

Helga and her mother barely had time to grieve before they were assigned to a transport. Before they left, Helga gave her diary and her drawings to her uncle, who hid them behind a wall in one of the Terezin barracks.

The Transport East

Helga and her mother’s transport arrived in Auschwitz a few days later. At fifteen, Helga realized she should lie about her age during the selection. She insisted she was eighteen and survived the selection. After ten days in Auschwitz, Helga and her mother were sent to Freiberg, Germany to work in an airplane factory. They worked in the unheated factory for twelve-hour shifts, with very little to eat or drink, and had to endure endless roll calls and the abuse of the guards.

As the Allies drew near, Helga and her mother were sent by rail to the camp Mauthausen, which took sixteen days. They were crammed into the train cars and endured days without food or water. As the train inched forward, they heard ear-shattering explosions from air raids and saw trainloads of wounded soldiers. By the time they arrived at Mauthausen, Helga and the other women had become emaciated, almost beyond recognition.

The conditions at Mauthausen were terrible, with food shortages, filthy, overcrowded bunks, and diseases like typhus were rampant. Incredibly, Helga and her mother survived, and were liberated by the Allies on May 5th, 1945.

Helga’s Life After the War

The two women made their way back to Prague, and ultimately managed to get their apartment back. Tragically, Helga’s father Otto never came home. But Helga and her mother Irena were never able to find out the truth about what happened to him. Most of their other relatives and friends never returned from the camps either. Helga’s uncle survived, and after the war, he was able to recover her diary and paintings.

Despite their grief, Helga and her mother knew they had to go on and build a new life for themselves. Helga enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague and began a long, successful career as a professional artist. She married a musician with the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra named Jírí Hošek. They had two children, and later, grandchildren. The artistic tradition continued into the next generations. Helga’s son and one of her granddaughters are professional cellists and another granddaughter is an artist.

The family remained in Prague, where Helga and her husband struggled as artists during the Communist era. For many years, Helga was unable to share her story. After the war, she found that no one wanted to know what had happened to the Jews of Prague.

Helga’s Diary

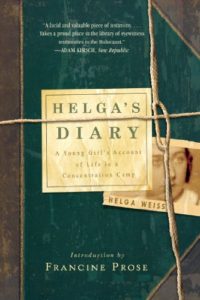

In the 1960s Helga published excerpts from her diary for the first time in a book about Terezin. Helga reflected that when she returned to her diary, she had so much more to express, more truths that she needed to share with the world. She ultimately began to expand on it and edit it for publication. Helga’s diary was published in English in 2013, under the title Helga’s Diary: A Young Girl’s Account of Life in a Concentration Camp.

Through her paintings and recently published diary, Helga has revealed the truth of Terezin to the world.

Further Reading

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/feb/22/helga-weiss-diary-nazi-death-camp

https://forward.com/news/319106/70-years-after-terezin-this-survivor-is-still-drawing-what-she-sees/