The Nazis brutally persecuted people with disabilities, and having any kind of disability could be a potential death sentence. And if someone was Jewish and had a disability,

their chance of survival was extremely low. Yet, in spite of these impossible odds,

there were gifted people with disabilities who left an indelible mark on the world, even

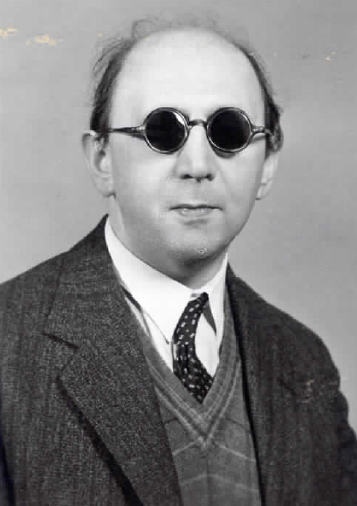

while imprisoned in a Nazi ghetto. And two of these individuals were Hans Neumeyer,

a pianist, composer, and music teacher and his older sister Irma, who had a gift for writing poetry.

Irma and Hans Neumeyer: Life Before Terezin

Almost nothing is known of Irma, or what her relationship with her brother was like. It’s known that she was an intelligent and thoughtful person, with a gift for writing poetry, as this manuscript reveals.

We know much more about Hans, who was born in Munich on September 13,1887 to a Jewish family. His father owned a men’s clothing store, and provided a comfortable life for his wife and children. As a child, Hans showed a strong aptitude for music. While still very young, he also developed an eye condition that caused him to slowly lose his vision. By the time Hans was 14, he was completely blind, but this didn’t hold him back from pursuing his music studies.

Hans later studied at the Academy of Music in Munich, graduating in 1909, and soon after co-authored a textbook on harmonics. He then taught at Hellerau, an

esteemed eurythmics center, where he met his future wife Vera Ephraim, one of the students.

In 1915, Hans set up his own music school with fellow musician Valeria Cratina, which they ran for the next ten years. He married Vera in 1920, and the couple settled in the artistic quarter of the city of Dachau. They had two children, Ruth and Raimund, who

they baptized as Protestants. Vera’s father was Jewish and her mother was Lutheran, and she was raised in her mother’s faith. Vera herself was very dedicated to the Lutheran faith and wanted her children baptized as well.

But when the Nazis came to power, neither Vera nor her children were spared from Nazi persecution. Ruth and Raimund were barred from attending school, from parks, swimming pools, and movie theaters. Then, on November 8, 1938 officials from the town hall knocked on the door and ordered Vera and the children to leave before dawn or else go to prison. Faced with the choice of leaving home or going to prison, they went to stay with one of Vera’s eurythmics students in Munich, where Hans joined them. But this was only

a temporary solution and the family had to move frequently.

At this stage, Hans’ sister Irma was living in a nursing home in Munich, since she was in frail health and had also lost her eyesight. Despite this, she would occasionally visit the family at their home. It’s unclear whether she continued to have contact with her brother and his family after they were forced to leave their home.

In May 1939, Ruth and Raimund were sent to England on a Kindertransport, where

they remained for the rest of the war. Hans and Vera intended to follow them, as Hans had secured a permit to go to a home for blind people in Leatherhead, just south of London. Tragically, Hans and Vera were never able to get out of Germany. The exact reason

is uncertain, but it seems likely that they were unable to get the permits to leave Germany.

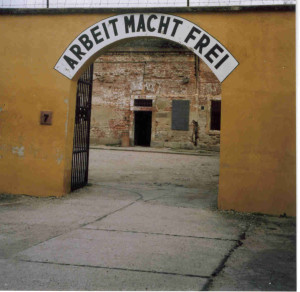

Irma Kuhn and Hans Neumeyer: Deportation to Terezin

In June 1942, Hans was deported to Terezin, where he was sent to live in a special barracks for people with disabilities. Irma was also deported to Terezin from the Munich nursing home in 1942. On July 13th, 1942, Vera was deported, either to Auschwitz or to the Warsaw ghetto, where she died.

Conditions in Terezin were horrific, with many thousands of people crammed together in a confined space, meager food rations, and rampant hunger and disease. But many people who survived Terezin remembered that conditions were especially terrible for elderly men and women and those with disabilities.

Since Hans was 55 and Irma was 68 years old and both were completely blind, their chance of long-term survival in Terezin was poor.

Yet Hans managed to survive in the camp far longer than anyone would have suspected, largely due to his musical gifts and resourcefulness. One day, Hans heard someone whistling Bach fugues and soon learned that this person was 17-year old Hans Ries, who was tasked with bringing food to sick and disabled inmates. Ries soon became a student of Hans, who gave him music lessons in exchange for soup and bread.

Hans began to take on more music students, including a 16-year old violinist named Thomas Mandl. Hans’ students called him “The Professor”, and those who

survived remembered him as a man of sharp intelligence and quick wit, who

always listened attentively to his students. While Hans had an easy smile, he possessed mental strength and toughness as well. Thomas Mandl remembered the calm and refined way Hans would eat his soup ration, despite the intense hunger he and the other

Terezin inmates lived with every day. And Hans never turned away a student who

couldn’t provide a bread or soup ration.

Hans taught his students a wide variety of topics, including harmony, intonation, rhythm, and counterpoint. One of his most successful students was Thomas, who

practiced diligently each night on the violin he’d brought into the ghetto. Hans

would listen to him play and offer suggestions for improvement. They often

discussed other topics as well, like politics and cultural events that were happening

in the ghetto.

The lessons continued until late 1943, when Hans contracted tuberculosis and was sent to a section of the ghetto infirmary for tuberculosis patients. Thomas and his other students continued to visit him when they could, and even from his sickbed Hans urged them to stay strong and not to lose hope.

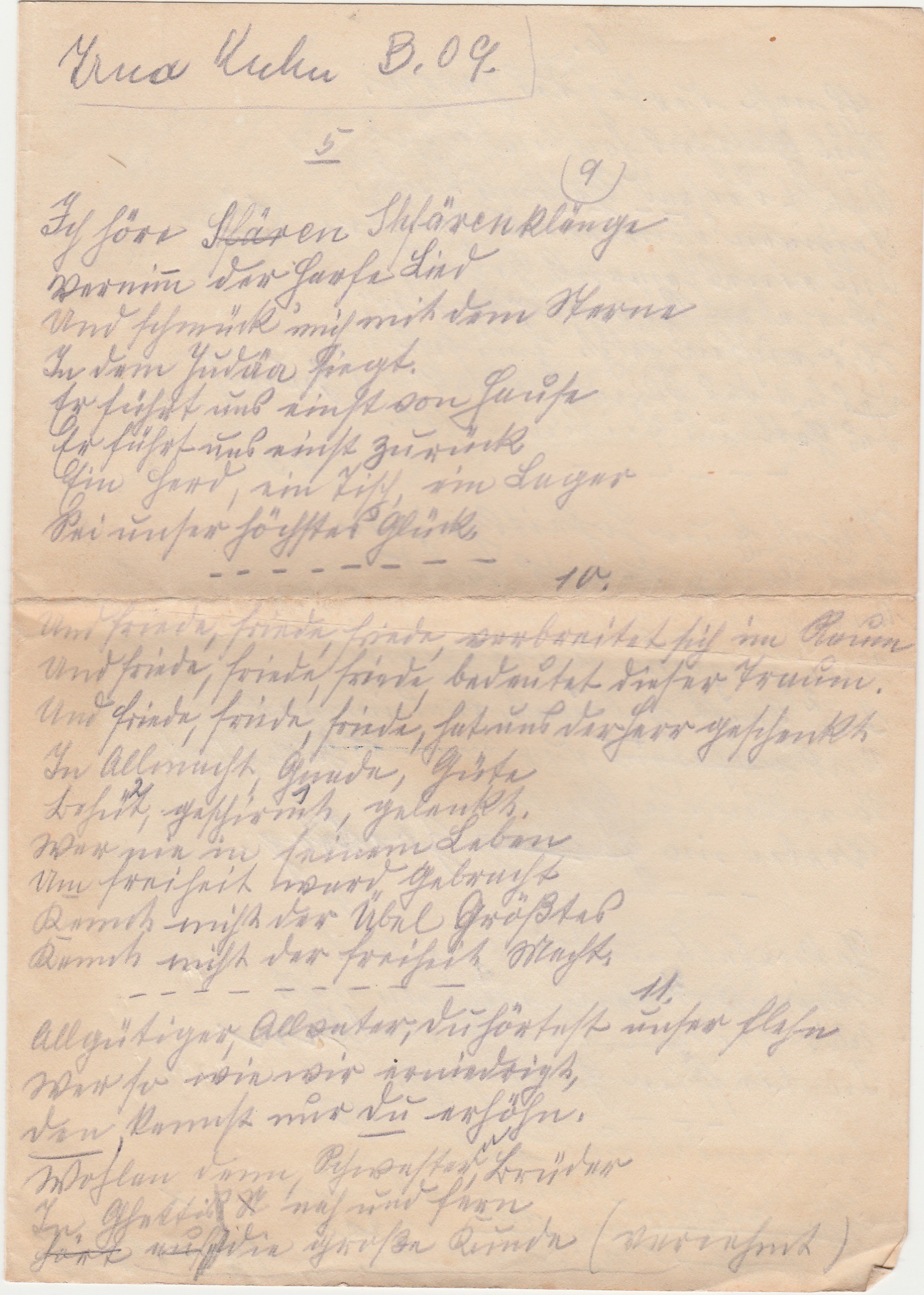

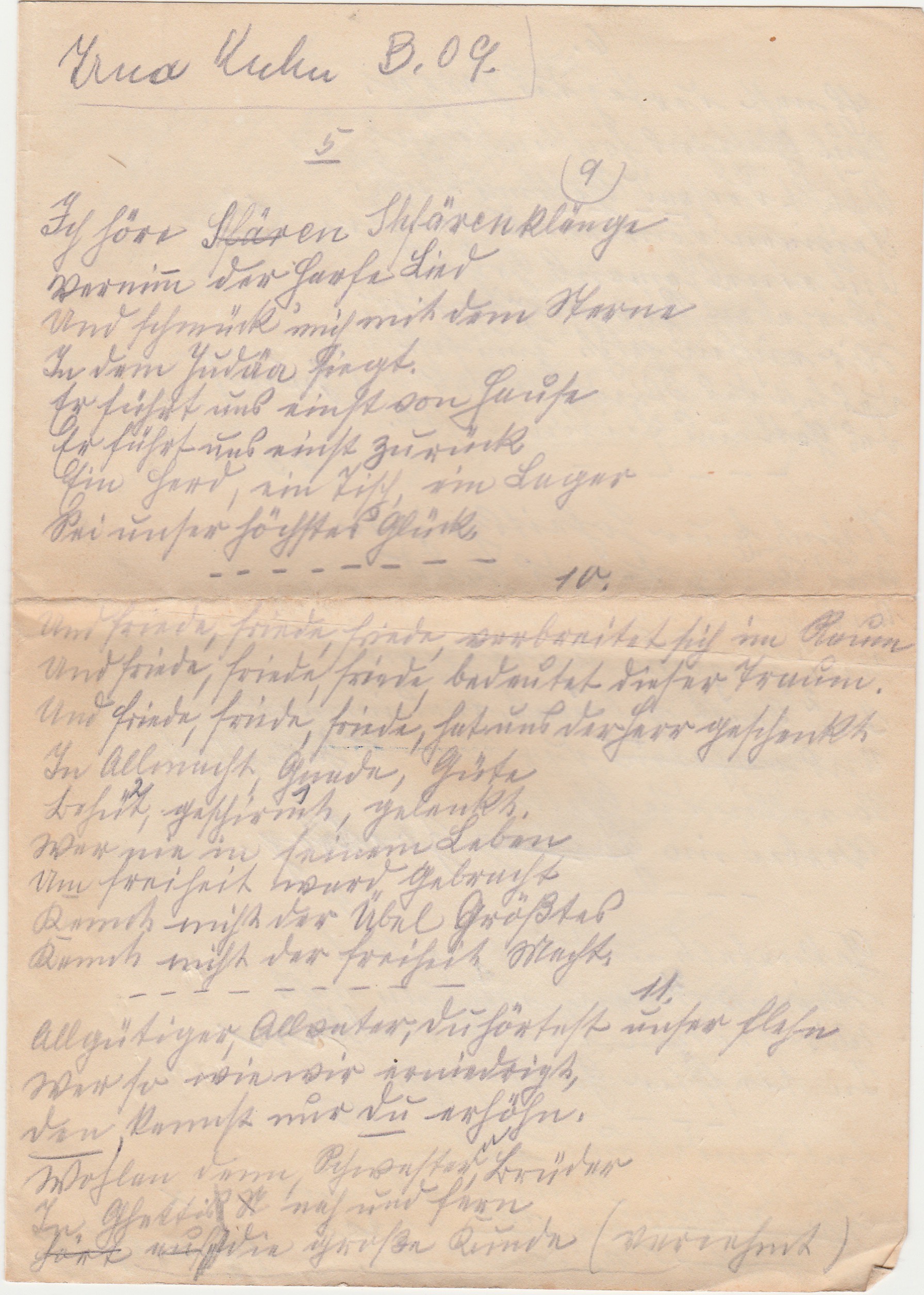

His sister Irma passed away in 1943, soon before Hans became ill. Little is known of Irma’s time in Terezin, but we know that she somehow managed to find her brother in the ghetto and reconnect with him. And during her time in Terezin, Irma composed a

deeply impassioned and intricate poem, which she dictated to another inmate.

The poem was dedicated to her brother Hans, and Irma presumably found

someone to deliver it to him. The poem’s imagery draws on Jewish symbolism

and tradition, and even expresses a hope for redemption, like in these powerful lines:

“I hear the sounds of the spheres

I hear the harp’s song

And I am adorned with the star

Within which Judea triumphs.

It leads us once from home

And will lead us back once more.

To our hearth, our table, our camp

It is our highest happiness.

And peace, peace, peace, will spread in the room

Peace signifies this dream

It is peace that the Lord has given us

In omnipotence, grace, goodness,

protected, shielded, guided

He who never in his life

Was deprived of freedom

Does not know the greatest evil

He does not know the power of freedom.

Most gracious Father of all, you have heard our plea

Those who are humiliated like us,

Only you can lift them up

Come then, sisters, brothers

In ghettos near and far

Hear the great news

The day of the Lord is near.”

Words and text copyright Tim Locke, 12.8.2022, translation by Lauren Leiderman. Used with permission of Tim Locke.

One can’t help but wonder if Irma wrote the poem for her brother intending him to set it to music. As he was teaching music in Theresienstadt, it seems likely that he would have wanted to compose as well. He could have dictated the music to one of his music students to write down.

It’s hard to imagine the depth of emotions that must have rushed through Hans when he received his sister’s poem. Sadly, his feelings about the poem remain unknown, as Hans died from tuberculosis in the spring of 1944.

The Legacy of Hans Neumeyer and Irma Kuhn

Little of Hans’s work survives, other than a string duo and string trio, a Christmas song written in December 1939 for his son Raimund, and two recorder duets written for his daughter Ruth in Easter 1940. Ruth and her brother remained in England after the war, and both eventually married and had families of their own.

Many years later, in 2005, Ruth recounted her family’s story to the Imperial War Museum in London. Ruth’s son Tim also commemorates Hans, Irma, and the rest of their family on a blog called The Ephraims and the Neumeyers.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of Hans’ and Irma’s surviving family, their legacy lives on, an incredible testament to their determination, resilience, and creative brilliance that the Nazis could never extinguish.

Further Reading

Irma’s Final Word From Theresienstadt

Mandl’s Testimony of Theresienstadt