Pavel Stransky and Vera Stadler’s Life Before the War

As Pavel relates in his account, As Messengers for the Victims, he met Vera during the summer of 1938, when both of their families vacationed in a small town in eastern Bohemia. 16-year-old Vera, a pretty, dark-haired girl, caught Pavel’s eye, and he invited her to go to a dance with him. As the months progressed, their relationship

blossomed, and by 1941, they were engaged

to be married.

The young couple struggled to retain hope for the future in the face of tremendous odds, including Nazi persecution and the tragic suicide of Pavel’s father. Drawing strength from the love he and Vera shared, Pavel underwent a teacher training course and accepted a job teaching Czech at the one remaining Jewish elementary school in Prague.

But Pavel never had the chance to start his teaching job. On December 1, 1941 he was transported to Terezin along with one thousand other young men. Not long after, Vera and her family arrived in Terezin on another transport.

A Terezin Ghetto Love Story

Upon their arrival, Vera and Pavel were assigned to barracks and given jobs in the camp. Pavel worked in a food warehouse as a porter while Vera was responsible for distributing meager food rations to the residents of Terezin.

After two incredibly difficult years in Terezin, Pavel was assigned to a transport in

the winter of 1943. In despair at the thought of being separated, and not knowing where the transport was heading, Pavel and Vera decided to get married. This would allow Vera to join him on the journey to the unknown.

Vera and Pavel married the night before the transport, under a makeshift cloth chuppah held up by four men. No wine was available for the ceremony, so the couple drank from a bowl filled with a bitter coffee substitute. There were no rings to exchange and no glass to step on, and they never even received a marriage contract.

The newly married couple spent their wedding night in a vast room with Vera’s mother and 2,500 other prisoners, sitting on their suitcases and holding hands as the hours passed. The next morning, the young couple was crammed into a cattle car with other prisoners, where they were forced to remain for days without food or water.

Auschwitz and the Czech Family Camp

Days later, the transport arrived at Auschwitz, where Pavel, Vera and thousands of

other exhausted and starving prisoners staggered from the cattle cars onto a

ramp illuminated by blazing spotlights. SS guards shouted at the prisoners and beat them as they forced the men away from the women and children. They grouped the new arrivals into rows of five and marched them from the ramp. No selection took place, and

no prisoners were sent to the gas chambers that night.

Pavel and the other men arrived at a large washroom, where they were forced to remove all their valuables and clothing. Then other prisoners shaved their bodies,

tattooed numbers on their left forearms, and then forced them to stand under freezing cold showers. Driven from the showers, Pavel and the other men had to wait outside in the icy air for hours, until other prisoners delivered threadbare uniforms and wooden shoes.

The treatment that Pavel and the other people on his transport received was different from what most new arrivals at Auschwitz experienced. Their heads were left unshaved,

and everyone on the transport – men, women, and children – were sent to one camp and housed in separate men’s and women’s blocks. This camp was known as the “Czech Family Camp”, and it was another Nazi hoax concocted to fool the Red Cross into thinking that

the prisoners were treated relatively well.

To keep the hoax going, the Nazis kept this camp filled with relatively healthy prisoners, most of whom arrived on transports from Terezin. Every six months, the Nazis

sent surviving prisoners to the gas chambers and replaced them with prisoners

from another transport.

Soon after arriving in the camp, Pavel was put to work carrying heavy rocks for use in the construction of a road, while Vera had to transport barrels of soup to the workers. In

an incredible act of love, Vera often risked her own life to smuggle extra rations of soup to Pavel so he could keep up his strength.

After a few days of this bone-breaking work, something remarkable happened due to the efforts of Fredy Hirsch, a gifted athlete and youth leader who also arrived in Auschwitz in September 1943. Determined to help the children in any way he could, Fredy

fearlessly approached Doctor Mengele and asked for permission to create a children’s block in the camp. Mengele agreed and put Fredy in charge of the children’s block.

Since Pavel had taken a teacher training course in Prague, he was assigned to be one of the coordinators of the children’s block. In this hell on earth, Pavel, Fredy, and several others did everything possible to improve the lives of these condemned children, to shield them from the horrors of camp life, and to provide them with fleeting moments of happiness.

They taught them songs and lessons from memory, organized art and poetry competitions, and helped them create skits and dances. Tragically, the devotion of Pavel and the other coordinators could not save these children, and almost all of them were murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Years after the war ended, Pavel remained haunted by the loss of these children, and could never stop wondering who they would have grown up to be, what gifts and contributions they would have made to the world.

Liberation and Life After Terezin

By June 1944, the Nazis were on the losing side of the war, and they made a desperate push to manufacture more weapons. They sent transports of healthier prisoners, including Pavel, to work in a factory at the Schwarzheide concentration camp. Vera was also chosen to work, and placed on a different transport to another factory.

At Schwarzheide, Pavel and the other prisoners were forced to work long hours clearing away the debris of Allied air raids. The conditions were unbearable, with meager rations, no hygiene options, and nothing to wear but ragged clothing, even in the bitter winter.

Then, in April 1945, all surviving prisoners at Schwarzheide were forced on a terrifying 19 day death march through the German countryside, back towards Terezin. Finally, on May 7th, 1945, the SS abruptly stopped the march and fled. There Pavel stood with his surviving companions, starving, ragged, and weighing just 70 pounds, but a free man at last.

Within days, Pavel returned to Prague with just one mission: to find his beloved Vera once again. As the months passed, Pavel gradually recovered his health and continued to search tirelessly for news of his wife, but learned nothing. Still, he refused to give into despair, and continued to hold out hope.

Then, two months later, the doorbell of the apartment where he was staying rang. Pavel opened the door, and was overwhelmed with emotion as he gazed at Vera standing right in front of him, looking as beautiful as ever.

Filled with indescribable joy at being reunited, they married a second time, this time under a real chuppah, with wine for the ceremony. They were never again separated in more than 50 years of marriage, during which time they raised four children and six grandchildren.

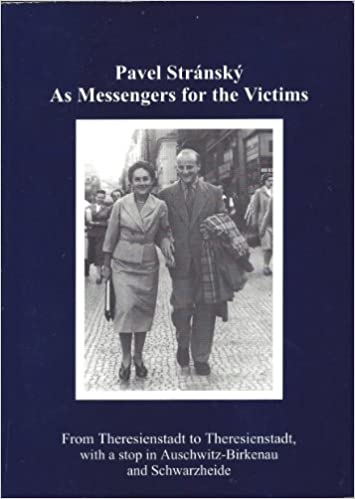

Pavel later wrote a book about their experiences during the war, and traveled to schools throughout Europe and the United States sharing their story with younger generations. He considered himself and Vera to be messengers for the victims of the Holocaust and after Vera’s death, Pavel continued his mission in her memory. In 2015 Pavel himself passed away, rejoining his beloved Vera once again.