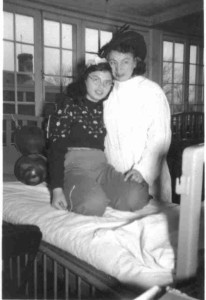

Helga Pollak was born in Vienna on May 28, 1930. Her father Otto was a disabled war veteran who owned a large concert café. When she was eight years old her parents divorced and Helga continued to live with her father. That same year, 1938, after the situation deteriorated for Jews in Austria, Helga’s parents sent her to Czechoslovakia.

Helga attended a German-speaking school in the city of Brno and had to live in a boardinghouse by herself. After Helga’s mother dropped her off in Brno, Helga watched her mother walk away and then went into a deserted room and sobbed. I could only imagine how terrifying and devastating this separation would be for a little girl. It is no wonder that Helga fell into a state of apathy and depression. Helga’s father ultimately arranged for her to stay with relatives in the town of Kyjov. She couldn’t speak Czech and had to repeat 2nd grade, but was much happier.

In 1939, Helga was supposed to travel to Great Britain as a child refugee, where she would join her mother, who had managed to emigrate there earlier. But after the German army invaded Poland and World War II began, the borders were closed, and Helga was trapped in Czechoslovakia. She would not see her mother again for nearly eight years.

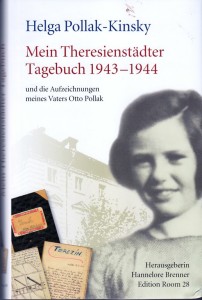

Beginning in 1943, Helga recorded many of her experiences in a diary. Many Jews kept diaries during the war, but except for Anne Frank’s iconic diary, most are not well known. While Anne’s diary is exceptionally well-written, she is too often depicted as a symbol for the suffering of Jewish children during the Holocaust. That risks downplaying her individuality and the way she perceived what was happening to her, and I fear it may have resulted in other war diaries being ignored.

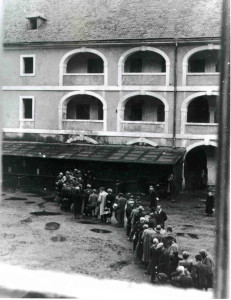

In the excerpts from Helga’s diary we see a sensitive girl who felt alienated from the girls in her barrack, and worried that they did not like her. We learn of her intense fears when her infant cousin Lea is seriously ill, and of her close relationship with her beloved father Otto. Helga also had moments of hope, of being deeply moved by the beauty of a sunset, for even Terezin’s walls could not block out the sky.

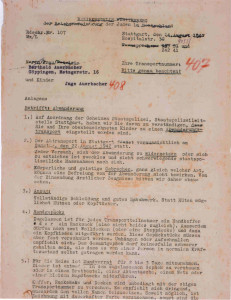

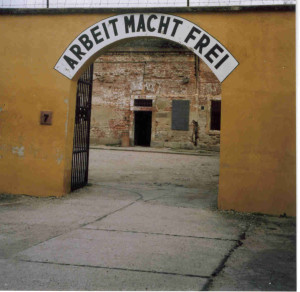

On October 23, 1944, Helga and some other girls from Room 28 were placed on a transport to Auschwitz. Helga survived the selection and vainly tried to search for her Lea, who she would never see again. She was sent from Auschwitz to different labor camps, and eventually returned to Terezin in late April 1945 where she was reunited with her father. The letter she wrote to him upon her return is deeply touching, as she so badly wanted to stay with him but could not because she was placed under quarantine.

Eventually she and her father were able to return to their surviving relatives in Kyjov, and the following year Helga went to England to join her mother. She completed high school and college, and later married a Prussian Jew who had fled to Bangkok to escape the Nazis. Helga and her husband lived in Thailand and Ethiopia until 1957, when they returned to Vienna with their children to be near Helga’s beloved father.

Though not published in its entirety, segments of her diary have been featured in the documentary films Terezin Diary and Voices of the Children and the main character of a play Ghetto Tears 1944: The Girls of Room 28 was based on Helga Pollak, the little known diarist of Terezin.

Further Reading

The Girls of Room 28: Friendship, Hope and Survival in Theresienstadt , by Hannelore Brenner