While conducting Terezin research I was surprised to discover that Czech literary icon Franz Kafka wasn’t the only talented writer in his family. Franz died in 1924 from tuberculosis and was spared the horrors of the Holocaust. Other members of his family were murdered by the Nazis, including his cousin, Georg Kafka, who was a talented poet and playwright.

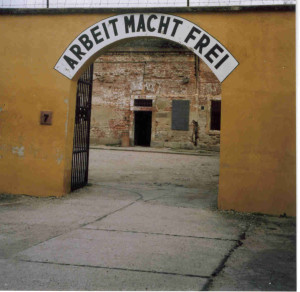

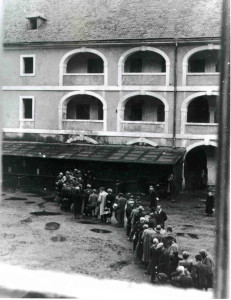

Little is known of Georg, but we do know he worked as a teacher until he and his parents were sent from Prague to Terezin when he was twenty-one years old, in the summer of 1942. In the ghetto, he managed to write poetry, fairy tales and plays, as well as translating contemporary Czech books into German. One of his most highly regarded works was a play in verse called The Death of Orpheus. It was selected by the Manes group, an organization in Terezin that promoted German-language plays and lectures. Phillip Manes, the leader of the group, spoke at the premiere of the play and praised Georg as a gifted and talented poet.

After reading the one-act drama, I found myself strongly agreeing with Manes. Typically, I find it a challenge to read the script of a play and feel that references to Greek mythology have been overdone. But I was engrossed by this play, which focuses on the extraordinary singer and musician Orpheus after he has lost his beloved Eurydice forever and has gone away to live among shepherds. Here Orpheus is a man defeated, no longer caring about even his music and trapped in despair. In an especially poignant scene, Orpheus is visited by his mother, who grieves to see what has become of her son, who was once so bright and full of life.

Georg Kafka could have become a great author in his own right, if only he had the chance. His father died in Terezin in March 1944, and Georg’s mother was assigned to a transport on May 15, 1944. Not wanting her to be alone, Georg volunteered to join the transport. His mother died, most likely murdered on arrival to Auschwitz, and Georg was later transported to a camp called Schwarzheide, where he died. After he was deported his work was remembered in Terezin, and he was awarded first prize in a poetry contest. It would be the final honor bestowed on this talented, creative young poet and playwright, the unknown cousin of Franz Kafka.

Further Reading (available on Amazon)

Performing Captivity, Performing Escape: Cabarets and Plays from the Terezin/Theresienstadt Ghetto

by Lisa Peschel (contains translation of The Death of Orpheus and short biography)