Though described as quiet and reserved, Ottla also demonstrated an independent streak. As a young woman, Ottla entered an agriculture program in which she was the only woman. The program was challenging in a number of ways, and Ottla had moments where she felt discouraged and considered leaving the program. Franz was supportive of his sister’s pursuit, but was also sensitive to the difficulties she faced. He assured her that there was no shame in leaving the program if she felt that was the right decision. Ottla persevered and ended up managing her brother-in-law’s farming estate in the northern Bohemian town of Zurau. Despite her father’s objections, she later married a Czech Catholic named Joseph David in 1920. The couple had two daughters, Vera and Helene. Life in central Europe following World War I was far from easy, and the family had to contend with food shortages, poor housing and widespread illness. Franz’s illness worsened, but he and Ottla still managed to meet occasionally until he died in 1924.

It was during World War II that the depth of Ottla’s courage and compassion became fully revealed. In 1942, as the deportation of Jews accelerated, Ottla divorced her husband, hoping that by disassociating herself from the family she could protect them from the Nazis. Soon after, she was deported to Terezin. Her daughters went to the police and begged to be allowed to join their mother, but their request was refused. Ottla’s daughters were never deported, and were able to remain with their father during the war.

In Terezin, Ottla helped to care for children who had been orphaned or abandoned as a children’s counselor. In 1943 she was selected to help care for a group of Polish children who arrived in Terezin from the Bialystock ghetto. The children were emaciated, with shaved heads, frightened eyes and would scream and cry in terror when taken to the showers. They were placed in a barrack separate from the other prisoners. Other prisoners were forbidden to interact with them and Ottla was forced to remain silent about her interactions with them. In 1943 the children were put on a transport to Auschwitz, and Ottla volunteered to go with them. She gave them what comfort she could in the final hours of their lives, what were to be the final hours of her life as well. Ottla and the children were murdered at Auschwitz upon arrival.

For many years Ottla’s daughters carefully preserved Franz’s letters to their mother. It was many years before Czech authorities allowed them to be published. Since then, they have been translated and published in English. Unfortunately, Ottla’s letters to Franz have never been found and are regarded as lost, which robs us of greater insight into this remarkable woman. This means that aside from historical facts, the most we know about Ottla as a person is what we can glean from letters written by the brother who adored her.

Further Reading

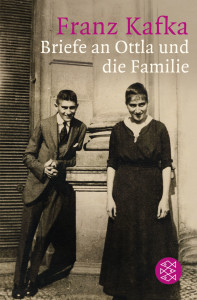

Letters to Ottla and the Family, by Franz Kafka